Potatoes collected and set aside during the Irish Potato Famine nearly 170 years ago are providing clues that will enable researchers to both better understand the cataclysmic event and also protect crops today.

Scientists at Rothamsted Research in Harpenden, a community in the English county of Hertfordshire, used DNA techniques on potato samples stored during the 19th century, according to the BBC.

Their research showed how the disease survived between growing seasons, and also helped scientist better devise tests for plant diseases going forward, the BBC added.

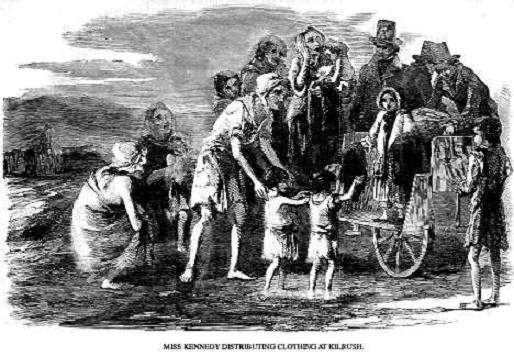

The Great Famine took place between 1845 and 1852 and claimed approximately 1 million lives. Another 1 million Irish emigrated, to escape the relentless hunger that struck after potato blight wreaked havoc on Ireland’s potato crop.

Fully one-third of the island’s population was entirely dependent on the potato for food.

Potato blight is caused by the microorganism, Phytophthora infestans, which destroys the leaves of potato crops.

Professor Bruce Fitt, who led the research, said there was an additional outbreak of potato blight about 30 years after the original famine, which sparked debate about whether it was the same pathogen strain from the 1840s, the BBC noted.

“In a given season it is spread by airborne spores but it also survives between seasons on tubers (the part of the potato plant that is eaten),” he said. “However, there was no evidence of how the pathogen survived between the 1840s and the 1870s.

“In a given season it is spread by airborne spores but it also survives between seasons on tubers (the part of the potato plant that is eaten),” he said. “However, there was no evidence of how the pathogen survived between the 1840s and the 1870s.

“They didn’t have the tools to investigate that but we can now use modern techniques to answer questions they couldn’t have dreamt of in the 19th century,” he added

Rothamsted scientists were able to extract DNA from potato samples dating back as far as the 1840s, analyzing tubers that had been dried, ground and stored in glass bottles by Victorian-era scientists for the presence of the blight pathogen.

“We wanted to see if it was the same strain and it was,” Fitt said. “It had survived between the 1840s and the 1870s between seasons on these potato tubers.”

Fitt added that the research, published in Plant Pathology, helped researchers better understand the spread of potato blight and proved the DNA technique would be useful for testing seed potatoes.

He said it could also be developed to test for other diseases which affect food production.

Blight still causes millions of dollars’ worth of damage today, despite the use of fungicides, the BBC noted.

Fascinating!

I thought so, too. And I appreciate the comment.

I love it when technology and history get together!

Some of my ancestors came to Australia to escape from the terrible conditions bought on by the potato blight. What an awful time it must have been.

We sometimes forget in today’s age of social security, unemployment relief and welfare that there was a time not too long ago when 10-20 percent of a nation’s population could starve or die of disease in a short period if the conditions were unfortunately aligned. Again, another reason to be grateful for what we have today.

In reading about the Canadian remains children, wondered if the possibilility that they were orphans deported by England:

https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2010/feb/20/margaret-humphreys-child-migrants-trust

“Children have been exported from Britain since the 1600s, though the practice only gained real pace in the late 1800s: from then until the 1920s, 100,000 were sent to Canada alone. Many of those who sent them seemed to have believed they were doing good, giving the children a new beginning; there seems, however, to have been no oversight of what the quality of this new beginning might be. In Canada, for instance, they were herded into distribution centres then sent, as free labour, to farms all across the country…”

I wonder this because in your article’s description of the “coffin ship” you state that bodies of the deceased were thrown overboard so frequently that sharks were known to follow the ships. So why would the children be taken to land & buried? You say the ships started in Ireland, then went to England & then crossed to Canada & had the poorest of the poor. The English “orphans” that were exported were often malnutritioned.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_Humphreys

Has anyone ruled out that these children’s remains were not English orphans deported to Canada & given a potters field burial?