The purported last Union officer killed in the War Between the States was a product of Harvard, shot down by a 14-year-old member of the Confederate home guard more than a week after Robert E. Lee had surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House.

Edward Lewis Stevens, Harvard Class of 1863, had enlisted as a private in the 44th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment on Sept. 12, 1862. The Brighton, Mass., native was 20 years old when he joined up.

He was later commissioned an officer in the famed 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, one of the first official African-American units and the subject of the 1989 film Glory.

Stevens was commissioned a 2nd lieutenant in the 54th in April 1864, nearly a year after the regiment had attempted to take Fort Wagner near Charleston, SC, where Col. Robert Gould Shaw and 280 other members of the unit were killed, wounded or listed as missing in action.

Stevens was promoted to 1st lieutenant in December 1864 and as the war would down, the 54th and other Federal troops found themselves back in South Carolina.

The 54th Massachusetts arrived in South Carolina on April 1, 1865, landing at Georgetown, between Charleston and Wilmington, NC, from Savannah, Ga.

The unit was one of six infantry regiments operating under Maj. Gen. Edward E. Potter, with the 54th contributing 700 officers and enlisted men to Potter’s 2,700-man force.

By April 18, 1865, Potter was in Camden, a medium-sized affluent community a little more than 100 miles northeast of Georgetown. That morning, Potter left Camden and headed south. They had traveled 10 miles on the Stateburg Road and encountered no opposition until they reached a fortified Confederate position at Boykin’s Mill.

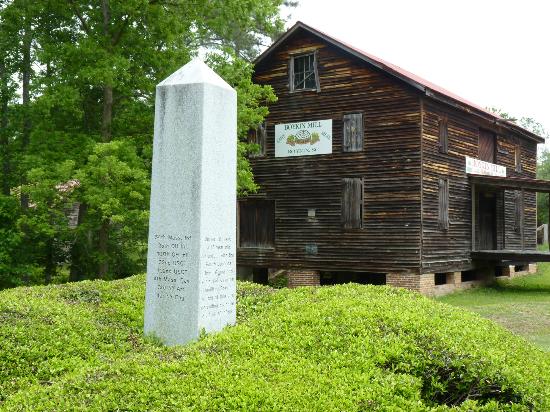

Boykin’s Mill was little more than a grist mill, church and small collection of homes, but its defense were enhanced by the presence of a millpond, along with streams and a swamp.

Southern troops had flooded the area and pulled up boards on the wagon road bridge in a bid to slow Potter’s men.

As Potter approached Boykin’s Mill, the bulk of the 800-strong Confederates force took up a defensive position on the opposite side of Swift Creek, which led into the millpond that served Boykin’s Mill.

In addition, the railroad bridge that crossed the swamp area a few hundred yards “west of the wagon road, was covered by enemy riflemen in trenches,” according to Leonne M. Hudson in a 2002 article in the Historical Journal of Massachusetts titled “The Role of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment in Potter’s Raid.”

With deep water preventing Union skirmishers from crossing Swift Creek, Potter turned to the 54th Massachusetts and told them to reconnoiter the left flank of the Confederate position. The regiment moved over plowed fields in search of a place to cross the creek but area blacks familiar with the region told them that there was no place to cross the swamp for at least two miles.

At that moment, a scout named Stephen W. Morehouse rushed to Maj. George Pope, telling him “there’s a lot of Rebs through there in a barn,” according to Hudson.

“Believing that quick action was necessary in order to avert a potentially dangerous situation, he led Company E to the place where the Confederates had congregated,” Hudson wrote. “The approach of the black troops caused the barn dwellers to abandon their sanctuary in favor of refuge on the other side of the stream.”

Pope ordered the company to hold that point while he scrambled to rejoin the 54th.

Exercising caution, the 54th continued toward Boykin’s Mill, understanding that they were the first Union troops nearing what appeared to be an enemy stronghold.

The men of the 54th came across a dike being used to dam the stream running through the mill. Captain Watson W. Bridge, commanded the skirmishers to cross the area but the effort was repulsed by a heavy volley that left two dead and four wounded from Company F of the 54th Massachusetts.

Col. Henry N. Hooper quickly realized the hopelessness of a frontal assault against the well-fortified Confederate position. He then ordered Pope to carry out a diversionary tactic a few hundred yards downstream. Pope and his four companies relied on “an old white-headed negro” to lead them through the swamps to a ford on Swift Creek, according to Hudson.

Pope instructed Lt. Stevens to make a demonstration toward the creek to attract the attention of the Confederate defenders. Just as Stevens had completed deploying his troops along the creek, the Confederates unleashed a storm of musketry fire.

Stevens was killed when he was shot in the head; two men from Company E were able to recover his body from Swift Creek.

The Federals were able to wrest the Confederate breastwork from the vastly outnumbered Southern forces by bringing up a cannon. A few well-placed shots from the field gun convinced the defenders that their position was untenable and they pulled back, ending the Battle of Boykin’s Mill.

It was to be the final action of the war for the famed 54th Massachusetts.

It is said that 14-year-old Burwell Henry Boykin fired the shot that claimed the life of Lt. Edward Lewis Stevens.

Burwell Boykin was anything but a barefoot country bumpkin who took advantage of the chaos of war’s end to fire off a potshot or two at invading Federal soldiers.

Boykin’s father was a Confederate officer who served as a captain in the 2nd South Carolina Cavalry Regiment under J.E.B. Stuart. The boy was on his home turf and said to have been defending his family’s land when he took up arms 150 years ago.

Born April 19, 1850, he would celebrate his 15th birthday the day after he shot Stevens.

Burwell Boykin would go on to marry Mary Deas Manning, the granddaughter of former SC Governor Richard Irvine Manning and niece of former Gov. John Lawrence Manning. He would live until 1934 and is buried in Camden’s noted Quaker Cemetery.

Lt. Stevens along with another member of the 54th, Corp. James P. Johnson, age 23, of Company F, were buried initially at Boykin’s Mill. Twenty years after war’s end, their bodies were disinterred and given a final burial at the National Cemetery at Florence, SC.

The Boykin family still owns the land the battle took place on, but they’re a bit more accommodating to outsiders these days.

In 1995, the Reactivated 54th Massachusetts Infantry approached Alice Boykin, owner of the surrounding property in Boykin, and asked if it could put up a monument to Lt. Edward L. Stevens.

“They wanted to put a monument up to Lt. Stevens,” Alice Boykin said in a 2008 article. “There aren’t too many monuments to Yankees in South Carolina. So, I told them that if they put a monument to both (Lt. Stevens and Burwell Boykin), that’s fine.”

The regiment erected the monument one-quarter mile from the battle site on the 130th anniversary of the clash, 20 years ago.

(Top: Boykin Mill, with monument to Lt. Edward L. Stevens and Burwell H. Boykin in foreground.)

wow –

Pingback: Potter’s Raid, April 18, 1865: “This last fight of the Fifty-fourth, and also one of the very last of the war” at Boykin’s Mill | To the Sound of the Guns

Very interesting. Thank you.

Thank you, Bruce.

speaking of your name, the Cotton Boll Conspiracy, I bought a lot of cotton seeds and will be attempting to grow them in new york state. It’s a potshot, although not with a gun. Have you ever grew it? I got a green, white, and brown variety.

I have grown cotton, as a matter of fact. Usually in small batches, 10-15 plants. You’ll want to wait until it gets warm, so I’d keep the plants indoors until it heats up a little more, if that’s still possible. It should get hot enough during the summer but they will need a bit of water occasionally. I’m not sure what the different varieties you have are, but they may germinate at different times, as well. I’d probably plant them in potting soil, as well, just to be safe.

Arkansas, red foliated, and brown mississippi http://www.southernexposure.com/cotton-c-19.html

How much does a plant produce? a big handful?

A healthy well-fertilized plant will produce 12-24 bolls of cotton. This picture shows several bolls after they’ve opened. http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/antenna/non-toxiccotton/images/cotton.jpg

Regarding the claim to the last Federal officer killed:

There may have been another the same day: George French of the 15th PA Cavalry was killed April 18 in Lincolnton NC during Stoneman’s Raid. French’s tombstone in Lincolnton calls him a captain, but some contemporary accounts say he was a corporal. Perhaps he was promoted posthumously. I wrote about him on my blog: http://stonemangazette.blogspot.com/2015/05/memorial-day-carolina-ladies-honor.html

Thanks for the information. Very interesting. It’s difficult to determine the “last” in many cases concerning the war due to poor recordkeeping that existed, particularly by the spring of 1865.

And it had to be a difficult “honor” for the families of those who lost loved ones at the very tail end of the conflict.